TRAVELOGUE / LIFE / MUSINGS

Corey Bell, Stage Traveler & Blogger

Music To Walk Home By:

Family Matters & Community at Bonnaroo

Volume XIII of

Eighty Thousand’s Company: The Modern Music Festival and the Pursuit of Community, Freedom, and Reverence in Personal and Collective Celebration

(click here to access All Volumes)

“The greatest thing you ever can do now, is trade a smile with someone who's blue now, it's very easy...”

--Led Zeppelin

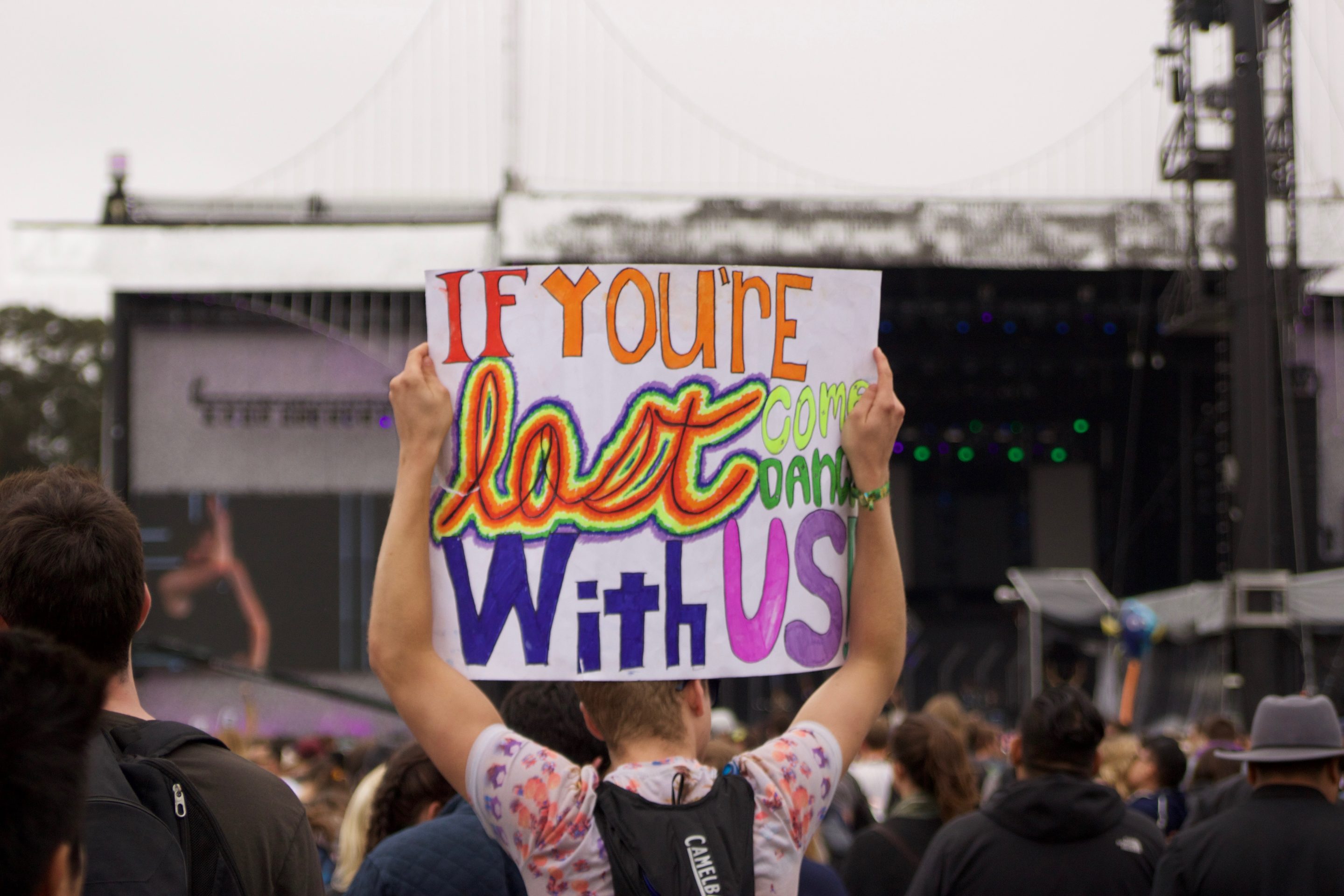

The sign says it all.

It all boils down to experience. We as festival-goers are just looking for something new to behold, some new song to hear, some new person to meet, some new story to tell. We all want to be a part of something memorable and fulfilling, and we want to experience it together.

To understand how the community of a music festival operates, one should have an idea of where these events come from historically. The idea of organized ritual dates back farther than any one can really trace. Ritualistic gatherings of people started way before any sort of recorded history, though the trend can be seen as far back as Dionysian festivals held by the Ancient Greeks, celebrating wine, food, music, and life (oh, how far we have fallen!). As Barbara Ehrenreich explains in her book, Dancing in the Streets: A History of Collective Joy, celebrations of the Middle Ages were only allowed on church holidays under strict supervision of the church. The basis of modern carnival came out of the oppression supplied by the church, after Catholic churches purged any sort of “unruly behavior.” Carnivals became disorderly, as nobody showed interest in church ceremonies during the festival, and thus the people turned to more secular activities, like dancing and games.

Fast forward to the 1950s and 1960s, when a rebellion of sorts broke out in opposition to the cold, puritanical society that had settled upon the UK and the United States over the past few centuries. Rock ‘n’ roll was the driving force behind this uprising, a new avenue for the release of long-oppressed sexual and expressive energy. In the cases of the Beatles and Elvis Presley, this new music allowed for the audience to abandon the propriety once expected of an audience, and to rejoice, instead of sitting quietly as one does at a symphony or opera. With clear roots in African percussive music, the music itself called to its listeners to stand up and dance, to move around and chant and scream, much like tribal circle dances. Authorities interpreted this new opposition as riotous, and often used force to quell this youthful display of defiance.

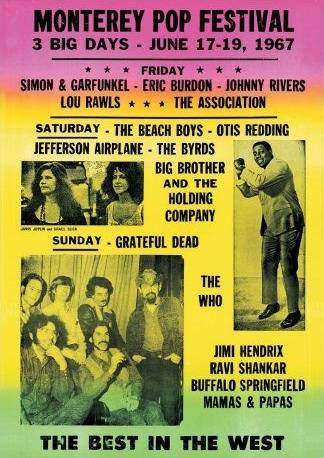

Advertisement for the Monterey Pop Festival.

But the young rockers would not give up. They sought freedom and expression, and rock music turned into a worldwide phenomenon. Due to the confinement of concert halls, rock musicians with massive fanbases had to find larger venues, resulting in the introduction of the outdoor festival. Folk and jazz festivals had already started popping up here and there, but the first real large-scale popular music festival was the Monterey Pop Festival, which inspired events like and Woodstock, as well as the festivals of Europe. In an interview with Tavis Smiley, Monterey Pop Festival founding member and charismatic songwriter Lou Adler spoke of the reasons behind putting on the first major popular music festival, explaining that “pop music wasn't considered an art form in the way that jazz was considered, and even folk. So when the opportunity came to purchase these dates in Monterey and do something, we thought, well, here's a chance to validate it.”

Monterey Pop in turn spawned the more (in)famous Woodstock, but after Woodstock, America didn’t seem to latch onto the idea of these massive outdoor events the same way that Europe did -- perhaps due to the chaos that ensued that fateful weekend in '69. Tons of festivals popped up in 1970 all across Europe, some that still go on to this day (The Netherlands’ Pinkpop and Finland’s Ruisrock have been going on annually since that time). It wasn’t until the ‘90s that the US got the bug. With the introduction of Lollapalooza in 1991 and Coachella in 1999, the American festival market started gaining some attention, and in 2002, Bonnaroo held it’s first ever event. They remain three of the largest festivals in the country, though Bonnaroo is the only one of the three whose philosophy is centered in the experience of camping at the festival all weekend (though there are others).

There are two types of major music festivals: ones that are based in or around cities that are mostly daytime events (ending somewhere between 10pm and midnight each night), and the ones that are often located in more rural areas that encourage camping, who face little to no time restrictions in regards to how late the event runs. Examples of the first kind are big city festivals like Lollapalooza, Governor’s Ball (NYC), or San Francisco’s Outside Lands festival, while events like Bonnaroo, the Sasquatch festival in Washington, and Southern California’s Lightning in a Bottle all fall under the umbrella of the more immersive ilk. Though there are seemingly countless examples of both, the trend these days seems to lean more towards the former, as they are easier to manage and are more likely to sell tickets. With the rising popularity of the culture—among patrons as well as artists (festival season is almost constant paying work for many artists)—in addition to the exponentially growing interest in electronic music, promoters are introducing dozens of new festivals each year, with no sign of slowing down at any time in the near future. The market is quickly becoming overinflated, and many lineups are so similar that the public’s interest is close to reversing altogether.

In other words, festivals are becoming so popular and abundant that they are starting to lose their appeal. Going to a festival is no longer as special as it once was, as practically anyone can get to one these days (if they can afford it; festival tickets are far from cheap). Of course they’re still fun and many—especially the ones that have been around for a long time—still boast impressive lineups that allow us to experience great music, but they are more crowded and expensive than ever. They have become so ingrained in the music industry that festival season has started to influence album releases. Not to mention that many have become veritable test labs for marketing strategies, and through corporate sponsorships some have basically turned into large- scale advertisements, shamelessly bombarding patrons with superfluous marketing imagery and signage. Sometimes it’s hardly noticeable, especially at smaller one- to two- day events; but other times it’s glaringly obvious, and it’s unsettling to see. Thankfully, at Bonnaroo, this has yet to happen.

"We get to know our neighbors. We share our supplies with those in need. We jump each other’s cars. Everyone’s got everyone else’s back, and moreover, we’re happy to do so."

The reason I’m saying all of this is because all this commercialism is taking its toll on the communities these events have the ability to nurture. While the daytime/non- camping festivals do bring people together and encourage micro-communities (i.e., getting all of your friends together and going to Coachella and having the best time), it’s only at the more immersive events—like Bonnaroo—where I have really felt the communal spirit. At events like Bonnaroo, you have the micro-communities (such as your group of friends, or your “fam” as some like to call it), and then there is the macro-community, which is the coming together of the population of Bonnaroo as a whole. Being continuously assaulted with marketing ploys would be frustrating and distracting, and would cause a rift amidst Bonnaroo’s faithful attendees.

The sprawling campgrounds of Bonnaroo.

At Bonnaroo, virtually everyone camps on-site (or brings an RV, or rents one of the tents or RVs on-site). There are some who spring for hotel packages and thus enjoy the comforts of temperature control, but I always feel like those people are missing out on what it means to really be at Bonnaroo. People travel from all over the world to attend this event, and for good reason. It’s a great place to connect with other people, people you would probably never have the chance to meet anywhere else. The people who go to Bonnaroo share not only their love of music, they yearn for the environment and the atmosphere that the community creates over the course of the weekend. It’s like a small city. Everyone pitches in to keep things running smoothly. We get to know our neighbors. We share our supplies with those in need. We jump each other’s cars. Everyone’s got everyone else’s back, and moreover, we’re happy to do so.

Back in 2015, I was on my way back to my camp one night when I realized I had lost the key to my friend’s truck. I frantically started retracing my steps back to Centeroo, iPhone flashlight in hand, scanning the path from side to side in the dark, trying to accomplish the impossible by finding a small black key in a mess of dark wet grass. Somewhere along the way, I caught the attention of someone sitting alone at his camp, and without hesitation, he came up to me, and asked me what I had lost and if I needed help. Not ten minutes later did I have a line of people following behind me, each crouched over with some sort of light source, searching the field for my lost key. We must’ve looked real silly, but I didn’t care. I was touched that these people were taking time out of their night to help me—a complete stranger—locate one lost item. We never did find the key ourselves, but someone did, as the next day it showed up in the lost and found. If it were anywhere else I wouldn’t have been able to believe it, but since I was at ‘Roo, it didn’t seem strange at all.

Later on that day I even ran into the first guy who offered to help me, and he stopped me to ask if I had found the key. I told him yes, he gave me a high five, clinked his beer can against mine, and went on his merry way.

Much like the Temporary Autonomous Zone (TAZ) developed by Hakim Bey— which serves as the basis for the philosophy behind Burning Man—Bonnaroo feels like a “pirate utopia.” It’s a haven for outsiders, a place where someone comes to feel like they belong somewhere. To me, it is and always will be a place that I feel comfortable calling home, and what’s a home without some family to share it with?

One of the coolest parts of being at Bonnaroo is witnessing how each “BonnaFam” operates, from the bright-eyed newbies who are unmistakable by their collective looks of constant wonder, to the seasoned veterans who have it all figured out. Each fam lives as one for the entirety of the weekend, and certain characteristics tend to make themselves known as time goes by. In the end, however, despite certain idiosyncrasies that define each individual’s specific role, and the inevitable partings that take place as tastes diverge and schedules bounce out of sync, it is as a whole unit that each family experiences Bonnaroo—and festivals like it, I am sure—for we all come together for those unmissable sets, those nights around the campsite, and in the memories we take with us after the farm is just a distant horizon waving at us in our rearview mirror.

Merrymakers at Outside Lands in San Francisco, waiting to be part of your big happy family ... for the weekend. 😛