EXPLORATIONS: SONIC HIGHWAYS

Corey Bell, Stage Traveler & Blogger

Another Travelin' Song:

A Wide Awake Bright Eyes Sings for Tomorrow

Part VIII of

Sonic Highways: Musical Immersion on the Roads of America

Back in the early spring of 2005, my friend Ian came to my father’s house in Connecticut for a night of clandestine cocktails, good conversation, and other time-honored traditions pertaining to the kind of old-fashioned adolescent merriment many of us enjoyed in the twilight years of high school. Nights like this were frequent in nature—weekly or biweekly—and very often were filled with tall tales, laughter, and fond memories in the making. In addition to trading stories and our respective stash of lifted libations, we would often find ourselves swapping music: current obsessions, longtime favorites, new discoveries…everything was fair game. When the Eroica started flowing, it became a game of oh-my-God-I-can’t-believe-you-haven’t-heard-this-album, a game we played well into our twenties as roommates in Brooklyn.

In the past, Ian had made it his life’s goal to tutor me in the irreverent teachings of Ani DiFranco, that deliciously brash and oft-outspoken folk musician/slam poet/badass motherfucker chick that was really pissed off for most of the 90s and early 00s but has since calmed down and mellowed out a bit. I took a different approach, appealing to Ian’s softer side through the velvety vocal caress of Canadian folk-singer-turned-Baroque-pop-icon Rufus Wainwright, among other things. Ian favored raw, high-powered, political/comic/slice-of-life songwriting; I liked pop songs with lush harmonies and eruptions of orchestral fury. I love the kind of song that tears through you with a well-placed swell of a full strings section right before hammering you in the temple with intense lyrical imagery, like a gargoyle war or an army of snake women as metaphors for crystal meth addiction.

On this night, however, our happy medium was found, in a piece of music so beautifully written and so terribly raw and relatable that I didn’t take it out of my car’s CD player for an entire decade. And it still remains one of my favorite albums of all time. That album was the fifth studio album belonging to the Omaha-based band Bright Eyes. Entitled I’m Wide Awake, It’s Morning, it is a seminal salute to folk music, the collective aching heart of a nation in pain, and a desperate optimism begging for a better tomorrow. And upon my first listen, I was its newfound devotee.

For those who are unfamiliar with the band, it consists of three permanent members that act as the epicenter around which a consistent, ever-changing deluge of collaborators and guest musicians swarm. They are well-beloved and revered, and to be involved with the band is somewhat of an honor within the realm of independently produced music. At the helm is the courageously blunt and politically charged pen and voice of Conor Oberst (also the front man of the punk group Desaparecidos, as well as the folk supergroup Monsters of Folk). Oberst’s signature trademarks are his silky, quavering voice, so majestically paired with his lyrics rooted in rampant anti-establishmentarianism and overall political unrest. Bright Eyes’ music—especially their earlier work—is somewhat notorious for being somewhat dismal and gloomy, though following the release of this particular album the band’s tone switched almost dramatically to one echoing the traditions of early Americana meshed with a generous helping of contemporary thought, bringing the older sounds into a more modern context.

I’m Wide Awake, It’s Morning was released in January of 2005 (mere months before the particular rendezvous between my friend and I) in conjunction with a more modern, electronic-tinged album entitled Digital Ash in a Digital Urn and was presented as somewhat of an antithesis to IWAIM. IWAIM somewhat effortlessly overshadowed the release of Digital Ash with its superior lyrical quality and a more empathetic human quality, one that has the ability to resonate with just about anyone. The instrumentation is fairly simple, relying on a handful of acoustic instruments (guitar, mandolin, pedal steel) with some electric guitar and bass tossed in, all driven forward by Oberst’s gravelly voice that gives the album’s ten songs a uniquely comforting timbre. The real star of the album’s many players is Oberst’s tantalizing, beautifully penned lyrics, invoking fantastic imagery and showing off impressive form in meter. Whether the song be arranged around one acoustic guitar or a whole slew of musicians drenched in a downpour of frontier-esque orchestration, the words – and the voice – always fit perfectly.

Ian had been a fan of Bright Eyes for quite some time before the release of I’m Wide Awake, It’s Morning, but this was my first encounter with them. Often is the case that the first song or album someone hears by any given artist or group ends up being their favorite. In my case, this unwritten rule has been proven to be true time after time, and I’m Wide Awake, It’s Morning is no exception. Since hearing this album for the first time, I have had the opportunity (and overall pleasure) of familiarizing myself with the rest of Bright Eyes’ impressive catalog, and I still hold true to my original opinion that this one still reigns supreme, and the reason is quite simple: I’m Wide Awake, It’s Morning possesses the best songs the band has ever written.

Moreover, the record makes for one hell of a road album, due to its organic sound and individual stories told within the album’s ten songs. The album’s opener, the thunderous “At The Bottom of Everything” begins with Oberst telling a tale of an ordinary woman on an ordinary flight, experiencing the same sort of mundane displeasure and inherent awkwardness we all succumb to on trans-oceanic flights (reading “long, really arduous magazine article[s]”, avoiding conversation with the stranger sitting next to you)…when all of a sudden, the plane suffers a “huge mechanical failure” and begins plummeting to the sea below. As the plane dives down, the man next to her starts “humming a little tune”, a tune which eventually blossoms into the song itself. The song itself is a grand invitation to challenge any and all boundaries forced upon us—both by societal norms/ideologies and our own insecurities—and does so with eloquent poetic nuance. The whole song is brilliantly composed—both musically and lyrically—and singling out any one verse as the best is simply impossible, yet here is one of my favorites:

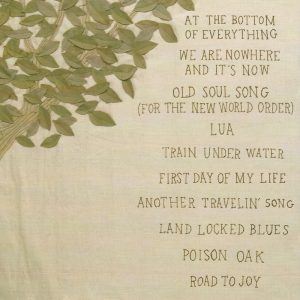

...and the back (w/ tracklist).

The front cover art....

We must hang up in the belfry

Where the bats and moonlight laugh

We must stare into a crystal ball

And only see the past

And into the caverns of tomorrow

With just our flashlights and our love

We must plunge, we must plunge, we must plunge.

These delicious words are backed by a romping, surprisingly deep-sounding symphony that is only made up of acoustic guitar, tickly mandolin, and a subtle bassline creeping underneath (it also features psych-rock outfit My Morning Jacket’s Jim James on backing vocals). In fact, the entirety of the album’s arrangement relies mainly on these three instruments, with a few tracks featuring decorative elements of organ, pedal steel, harmonica, and trumpet that playfully yet powerfully enhance the core instruments.

“At the Bottom of Everything” vividly sets the album’s wild and ravenous tone that is carried throughout, even in the album’s slower, more somber moments, such as the delicate requiem for a loved one’s descent into addiction (“Lua”) and the melancholy sounds of “Poison Oak,” a tragic soliloquy lamenting the loss of a childhood friend. Even though these two tracks are almost polar opposites of the booming, in-your-face opener, they carry with them the same sort of relatable realism that echoes from each song’s simple, yet poignant guitar riffs, and drips from Oberst’s pouty, stinging words. The album’s eighth song, “Landlocked Blues,” details a painful separation within a toxic relationship on mutually agreeable terms, though the necessity to split—despite it ultimately being the right decision—offers no comfort to the song’s protagonist. It further deepens the emotional range of the album as a whole, while at the same time keeps everything strikingly relevant and thus comprehensible to a wide audience, most of whom, undoubtedly, have been in similar situations. Empathy is what truly builds a devoted audience. Those who are able to physically feel the stinging agony emanating from Oberst’s dark and fluttery vocals are the ones who are going to resonate with his music. And who hasn’t felt that kind of pain before?

Most of the album’s middle tracks exhibit the same sort of fragile tenderness as the three aforementioned ballads. The adorable charm of “First Day of My Life” celebrates budding romance as a gift, gushing with optimism that is not often found in Bright Eyes songs, while the second track “We Are Nowhere and It’s Now” finds its footing as a tale of one lost in the clutches of an existential crisis who seeks solace in the simple joys of life. In true Conor Oberst fashion, the album takes a turn as an arena for social commentary with “Old Soul Song (For the New World Order),” telling a tale of an uprising against the government and an ineffable search for truth and beauty, and the hope they may eventually intersect.

You may be scratching your head at this point as to how any of this makes for a good album for the road, and I promise I’m going to get there, but this sort of exposition is necessary, so you can understand what the album is all about. While none of the songs I have described for you have no obvious connection to roads, or cars, or even travel in general, there is an unshakeable urgency for progress that permeates throughout the album…whether it’s a call to arms for a new world order, or the need to separate oneself from something or someone they love just to save themselves, or even the prospect of a new opportunity for happiness; there is a fascination with the idea of moving forward.

"Empathy is what truly builds a devoted audience."

The message is not only translated in the obvious way (i.e., the lyrics), but it is also reflected in the composition of the accompanying score. Music has an uncanny ability to tug at our heartstrings in a way that some find hard to articulate verbally, and I am certainly no exception. Most of the emotions we feel while listening to music generally fall somewhere amongst joy, transcendence, empowerment, and nostalgia. The inviting acoustic arrangements are matched with a sonic landscape that carefully dips and rises in regard to tempo, tone, and timbre, which makes it an especially good album to travel with. Such composition has the ability to mimic a great variety of landscapes, almost as if the musicians are in the car with you, taking cues from the surrounding environment in an effort to provide the ideal music for the journey. The bright sounds of the mandolin and acoustic guitar throughout reflect a certain sense of positivity that carries us along, conjuring images of an endless road ahead, rife with possibility.

Such buoyancy runs rampant throughout the album’s central track, aptly titled (for this purpose, anyway) “Another Travelin’ Song”. It’s probably the most upbeat and exciting song on the record, with thumping percussion compelling the strong-handed central guitar riffs along, punctuated with momentary distorted pedal steel swoops mimicking the sounds of distant train whistles, summoning the image of a jet black locomotive blazing through the desert at breakneck speed. If that image doesn’t inspire a sense of power and whet your appetite for the open road, I don’t know what will.

The fifth track, a song called “Train Under Water,” romanticizes the tranquility and promise of the old west within a contemporary context, as the train in question is not an old-fashioned steam train rocketing across the plains, but in fact, New York City’s “L” subway line, yet you would never guess it if you didn’t listen carefully to Oberst’s playful lyrics. The song itself sounds like a Willie Nelson cover, delivering a gentle, swaying guitar riff amidst a shower of elongated pedal steel notes and breezy harmonica.

I have a very clear memory of the first time I heard this album on the road. Again, I was with my friend Ian, on our way to Tennessee for the Bonnaroo Music Festival. It was early June of 2005, and Ian and I had only graduated from high school the day before. After a laborious nightlong drive through the upper mid-Atlantic and a brief, three-hour nap at a Maryland hotel, we finally crossed into Virginia just as the sun began to peek out from behind the horizon. Our hearts swelled with excitement: there was only one state between us and Tennessee. It was the home stretch.

Or so we thought.

Unfortunately for us, the stretch of Interstate 81 that meanders through Virginia down to the southwest goes on for a whopping 325 miles. Depending on how fast you drive, that can take up to six hours to traverse. However, the drive proved to be quite scenic as it snaked its way down through the picturesque Shenandoah Valley, carved out of rolling hills and flanked by blue-tinted mountains to the south.

By this time, I was basically obsessed with I’m Wide Awake, It’s Morning, and it had become mine and Ian’s personal soundtrack, underscoring most of our hangouts and the numerous long car rides along New England’s highways (we grew up in the boonies, so it took at least twenty minutes to get just about anywhere). Oddly enough, we hadn’t played it during the entire trip up to that point. Not even once. As the landscape began to shift and the road started to bend and dip, it just clicked. The sun was high in the sky by this point, pouring in through the sunroof of my weathered, dusty-blue ’95 Honda Odyssey, and the thousands of leaves on the trees bordering the highway glowed green with envy, jealous of our youthful ambition. It just felt right.

So, I put it on, and we sung along fervently, barreling down the highway and attracting a curious glance here and there from the cars we passed. The album acted as the heartbeat of that particular leg of the journey, the pulse pushing our shoddy blue van through the bloodstreams of America’s highways. When the album’s closing track—the cacophonous “Road to Joy”—came on, the spirit of the music had possessed us, forcing us to sway and drum and swing our heads as the loud and jubilant words flew from our mouths in sync with Oberst’s. By the time we reached the Tennessee border, we had shed our accumulated aggravation caused by the strenuous journey taken along the ever-vanishing roads behind us, revitalized by our imminent destination.

But it wasn’t just because we were getting closer that we felt this sense of rebirth; Bright Eyes’ I’m Wide Awake, It’s Morning had awakened a new hope within us. Not only was the vastness of Tennessee ahead of us, but so much more as well. We felt the prospect of the real world, filled with opportunity; and the great unknown, the broken hearts and broken promises that would mend and be forgiven, and the chance to witness the birth and death of tomorrow. We were barreling into reality at warp speed, taking it all in as we tapped our feet and bobbed our heads to the music, driving, wild and free, into the sunset.